AAUW has been encouraging and supporting women for years. To see how AAUW has changed the lives of many women watch this you tube video about AAUW contributions

While we compile the history of AAUW Sarasota Branch, we were lucky enough to have a presentation about AAUW’s historical contribution to the Women’s Suffrage Movement. That presentation is below. Please continue to check back as we’ll more history in coming months.

AAUW SUFFRAGE PRESENTATION

By June Melby Benowitz

September 2019

When Diana Sells, our Branch President, invited me to research and possibly give a presentation on the AAUW and the campaign for woman suffrage prior to the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, she warned me that the organization did not appear to be deeply involved in that campaign. Upon looking into the early decades of the history of what would become the AAUW, I found that Diana was correct. In fact, I found that this organization did not take on the title American Association of University Women until 1921, one year after women acquired suffrage.

Thankfully, the story of the AAUW and suffrage does not stop there. Just as I am sure that most women in this room belong to organizations beyond the AAUW, so did women of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. And, I found some connections between the AAUW and the suffrage movement.

Having researched and taught women’s history during my career as a history professor, I was not really surprised to notice some familiar names when reading about the early years of the Association of Collegiate Alumnae, or ACA. The ACA was the name of the original organization that would eventually join with others to form the AAUW in 1921.

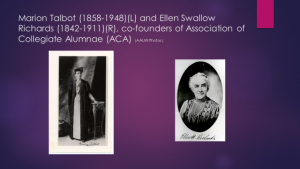

Marion Talbot and Ellen Swallow Richards are considered the co-founders of the ACA/AAUW as they organized a meeting of women who would make plans to form such a group.

Talbot, age 23 in 1881, was completing a master’s degree at Boston University at the time but realized that there were few employment opportunities for young women with college degrees.

Richards, who was 39, had been the first female accepted into the Massachusetts Institute of Technology as a “special student” experiment to see if women could succeed in studies in the sciences, but although she successfully completed the required courses in her field of chemistry, she was not granted a degree. Nevertheless, she did serve as an assistant instructor – without pay.

While both Talbot and Richards pushed for greater rights and opportunities for educated women, I found no evidence of their being involved with the campaign to give American women the right to vote.

Talbot and Richards arranged for a meeting at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology on Nov. 23, 1881, and 17 women attended. They represented 8 colleges and universities. Most were recent graduates. By the end of the meeting the women agreed to hold another meeting on January 14, 1882.

Sixty-five women attended this meeting. It was among these women that I found names of some who were active or would become active in the movement for woman suffrage.

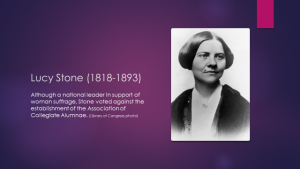

With one exception, all of the attendees had graduated from college in either the 1870s or early 1880s. The exception was Lucy Stone, a graduate of Oberlin in 1847 – the first woman from Massachusetts to graduate from college. Oberlin was the first college in the US to accept both women and African Americans. Although women were admitted, they were expected to do laundry for male students.

The women at the 1882 meeting voted to establish an organization, calling itself the Association of Collegiate Alumnae (ACA) that would push to set a standard for the higher education of women, and help to make it a valued thing for girls to attend college. They wanted their organization to be supportive of young women who chose to leave colleges for occupations that were normally held by men.

Only one of the 65 attendees disagreed with the project. That was Lucy Stone (1818-1893), who was known nationally as a pioneer for women’s rights.

Stone expressed doubt as to the need for such an organization and was clear in stating that she saw no methods by which its purposes could be accomplished.

I find this interesting since Stone had begun speaking out in support of women’s rights and against slavery in 1847.

At the National Woman’s Rights Convention in Cincinnati in 1855, she gave a speech that became famous as her “disappointment” speech. In it, she noted that women were disappointed “in education, in marriage, in religion, in everything, disappointment is the lot of woman. It shall be the business of my life to deepen this disappointment in every woman’s heart until she bows down to it no longer.” She, along with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and other women’s rights leaders, actively circulated petitions throughout the US, demanding voting rights for women.

The women’s movement split in 1869. The split came about largely due to differing viewpoints regarding the proposed 15th Amendment to the US Constitution, which would prohibit the denial of suffrage on the basis of race. Anthony and Stanton campaigned against the amendment due to its not including enfranchisement for women. While not happy that women were not included in the amendment, Stone supported it. Anthony and Stanton formed the National Woman Suffrage Association while Stone was a leader of the American Woman Suffrage Association.

While the NWSA sought greater rights and opportunities for all classes of women, and addressed a variety of issues, including women’s rights in marriage, divorce, and employment, the AWSA was made up of upper classes, better educated women, and focused its attention solely on granting women the right to vote. This focus may be the main reason Stone opposed the organization of the ACA.

Despite Stone’s pessimistic point of view, the other women at the meeting went ahead and adopted a constitution, elected officers, and established the Association of Collegiate Alumnae.

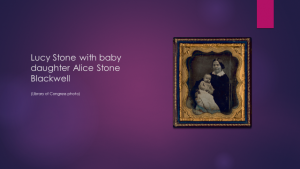

Among the 64 women who voted in favor of establishing the ACA was Lucy Stone’s daughter, Alice Stone Blackwell. At the time of the ACA’s founding Blackwell was 24 years old, and a recent graduate of Boston University, where she had been president of her class.

Like her mother (and father Henry Blackwell too) Alice worked in support of women’s rights. In 1890 she helped reconcile the two competing suffrage associations. After being split for more than 20 years, the American Woman Suffrage Association and National Woman Suffrage Association reunited to form the National American Woman Suffrage Assn.

Meanwhile, Blackwell was active with the ACA at least into the 1910s.

Another person who became a prominent member of the ACA was educator M. Carey Thomas.

Thomas, born in 1857, graduated from Cornell University in 1877, and went on to do graduate work in Greek at Johns Hopkins University, but withdrew because, due to her being a woman, she was not permitted to attend classes. She traveled overseas to attend the University of Zurich, where she earned a Ph.D.

When she returned to the United States in 1883, she was aware that plans were underway to establish Bryn Mawr College for women. With the help of family connections, she hoped to become the college’s first president.

She was made Dean of the college when Bryn Mawr opened in 1885, but did not become its president until 1894.

In the process of researching ideas for establishing a successful college, in 1884 Thomas toured colleges that had female faculty members and/or were women’s colleges.

One of the first women she met was ACA/AAUW co-founder Ellen Swallow Richards. Richards introduced her to other female educators. One of those women was the other co-founder, Marion Talbot, who Thomas found the “most attractive” of the “many clever women” she met in her tour of Boston’s educational institutions.

Thomas’s work in creating Bryn Mawr was located squarely in her commitment to the cause of women. She aspired to give young women the best education possible.

She sought to hire the best and brightest professors – as long as they weren’t Jewish. She did allow for the admission of a few Jewish students. Even for that time, she was especially anti-Semitic.

One of the first faculty was Bryn Mawr’s history instructor, Woodrow Wilson.

Between the years 1898 and 1906 Thomas held the reputation of the leading national spokeswoman for women’s higher education and a top college president. She believed that the career paths of men and women should be identical, and that all fields and positions should be open to women.

By the early 20th c. Thomas was a committed suffragist. She associated with suffrage leaders but was initially hesitant to give speeches in support of suffrage for fear of alienating the more conservative parents of Bryn Mawr students. (Bryn Mawr was a Quaker college)

In 1902 suffrage leader Susan B. Anthony, who was in her 80s at the time, was an honored guest at Bryn Mawr.

By this time, Thomas was becoming active with the Association of Collegiate Alumnae, which would later become the AAUW. She gave a number of convention addresses and served for some time as President.

Thomas addressed the ACA at its 25th anniversary convention in 1907, where she argued for the value of women’s graduate school. The world needs more female scholars who can serve as guides for younger women students, she said.

In 1905 Susan B. Anthony was an invited guest for the second time at Bryn Mawr. This time she was accompanied by NAWSA president Anna Howard Shaw.

Thomas’ public support of suffrage was buttressed by class consciousness. It bothered her that as a Ph.D. and president of a college, she was not able to vote, yet all male employees at the college, from faculty members to grounds keepers, could vote.

But NAWSA itself was also elitist, focusing on educated white women.

At the NAWSA convention in Buffalo in 1908, there was a call for college chapters to form the National College Equal Suffrage League under the NAWSA umbrella. Thomas assumed the presidency of the new organization. She also claimed that the idea for the league was hers.

Until it disbanded in 1917, the NCESL sought to bring debate into college campuses and to rally educated women to support suffrage.

Thomas’ special gift was her oratory. In her speeches she was able to bridge differences between northern and southern women, as well as speak to multiple generations.

After women won the vote in 1920, Thomas continued her support for women’s rights, and made a public name for herself in her support for the Equal Rights Amendment proposed by Alice Paul of the National Woman’s Party. Thomas remained a supporter of women’s rights up to her death on Dec. 2, 1935.

Because most of the ACA members lived in the Northeastern US, some living in the West felt left out of discussion and found themselves unable to harmonize their plans with their New England counterparts. These women founded an independent organization, known as the Western Association of Collegiate Alumnae, in 1884. However, the 2 groups had reunited under the ACA title in 1889.

A third group, the Southern Association of College Women, was founded in Knoxville, TN in July 1903. (In 1903, there were more than 140 Southern institutions calling themselves “colleges for women,” but only 2 of them offered 4 years of college.) From its beginning, the ACA took particular care to grant membership to women who had attended colleges known for having high educational standards.

It wasn’t until 1921, after woman suffrage became law, that the Southern Association merged with the ACA, and they became the American Association of University Women. Meanwhile, in 1915 the national ACA officially voiced support for woman suffrage.

Selected Sources:

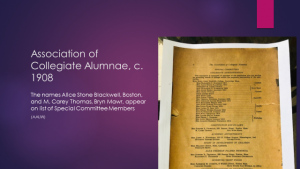

AAUW, “Register of the Association of Collegiate Alumnae”, 1908 Supplement

Gould, Susan, “AAUW’s Long Road to Women’s Suffrage,” www.aauw.org/2013/08/23/road-to-womens-suffrage/.

Horowitz, Helen Lefkowitz, The Power and Passion of M. Carey Thomas (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994)

Levine, Susan, Degrees of Equality: The American Association of University Women and the Challenge of Twentieth-Century Feminism (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1995)Warming, Katherine, “American Association of University Women,” in Women in the American Political System, Vol. I, pp. 17-19 (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2019)